- Results cannot be predicted from the separate actions.

- Strategies depend on others’ strategies.

- Behavior changes the environment.

For my Bachelor’s dissertation I have delved into the approach to International Relations Theory based on Complexity studies, grounding the account into what Robert Jervis proposes in his book System Effects. This understanding of international relations puts classic conceptions of levels of analysis into question. A long-lasting debate on which should be the fundamental unit of analysis for an IR (International Relations) theory has characterized the discipline and any theoretical proposal has provided its views and assumptions regarding this problem[1]. Thus, in presenting the complexity approach to IR, it is necessary to make clear its stance on that as well.

The historical debate has considered mainly three levels of analysis: individuals, states and system. These ones go from the lower level to the higher, and even if the second one is sometimes eluded[2], the logic of such scheme can be easily grasped. On one extreme, liberalism[3] has historically preferred the first level, as people express and act accordingly to their preferences and interests and then form higher levels’ behavior and effects. Gender approaches[4] second these liberal assumptions, focusing on individuals’ issues and relative power of different genders.

The historical debate has considered mainly three levels of analysis: individuals, states and system. These ones go from the lower level to the higher, and even if the second one is sometimes eluded[2], the logic of such scheme can be easily grasped. On one extreme, liberalism[3] has historically preferred the first level, as people express and act accordingly to their preferences and interests and then form higher levels’ behavior and effects. Gender approaches[4] second these liberal assumptions, focusing on individuals’ issues and relative power of different genders.

On the other extreme, neorealism[5] has argued for the dominance of system in international life, since systemic constraints form units’ decisions and their positions in the system is more important than their internal features. World-system theory by Immanuel Wallenstein[6] behaves similarly, and neo-institutionalist stances[7] on systemic uncertainties and lack of trust lay on the same grounds. The middle level of states is more complicated to ascribe to specific theories. It can be seen as the intermediate level where neither pure systemic dynamics nor individuals’ preferences are predominant over groups’ interests, which then become interesting to analyze here. Indeed, in a contemporary perspective, actors more than states should be considered on this level, e.g. international organizations, multinationals, non-state actors, terrorist affiliations and so on. They are not individuals acting on their single interest neither they are the whole system with its structure. They are units of the international system, but also systems that contain lower units, i.e. people. Various theories focus on this level, such as liberalism with its strength on foreign policy analysis or constructivism with its studies of national identities[8]. Post-structuralism analyzes discourses and narratives of groups[9]. It criticizes system thinking as it believes that systemic theories prefer totalizing and static systems, distant from political realities (and from what complexity theory thinks about systems).[10]

In complex systems, all features play a role to produce final outcomes, and because of the ‘butterfly effect’ none should be analytically excluded. This approach takes all the three mentioned levels of analysis into account, as all elements within a system interact and the relations between units and systems are reciprocal (units adapt to system and it adapts to them, and both change eventually). Considering various agents and keeping a systemic mindset at the same time becomes fundamental in a complex and interconnected world. The described features of complex systems clarify this stance of a complexity approach to IR.

In a complex networked reality as the present one, interactions become central. In systems relations are not defined bilaterally, since there are always some other actors at play who have certain interests about the outcomes. Countries can benefit or be endangered by changes in relations among others, over which they do not have control. Third parties are always affected by others’ actions, as effects spread throughout the system. This explains why local perspectives are ineffective to present international issues, and why states have gone to wars with whom they did not have direct conflicts (here the examples of the World Wars can be significant). Stating that effects on variables depend on which others are present within the interactions, challenges the “democratic peace theory”: democracies might be united and peaceful at the moment in order to counter or distinguish from autocracies, but once triumphant they may turn on one another[11].

To counter partial and limited views of mainstream IR theories, the complexity approach takes an interactionist perspective. Interactions can be analyzed through three main kinds, that help clarifying the facets of such position well outlined by Jervis:

- Results cannot be predicted from the separate actions.

This first feature reiterates the non-additive nature of complex systems, namely the fact that such systems are different from the mere sum of their parts, as interconnections and networks raise an irreducible complexity. Results can differ a lot depending on actors’ choices and moves, since effects of one variable often depend on others. Thus, extension and direction of elements’ interactions depend on the status of others. “In the example of combined arms tactics, the answer to the question of how we might best invest any additional dollar of defense spending might vary depending not only on the enemy we expect to fight, but also on the existing levels of each kind of arms”[12]. It follows that complex systems fail as several elements fail too, while if they were not interacting they would have been harmless to the whole.

Important lessons follow. Studies of changes in results often flawed by focusing on a single factor, assuming that others are constant[13]. It is common to examine just one side and overlook the other which the former is interacting with. Conversely, it is necessary to pay attention to others’ interests and actions. This perspective better explains failures and successes of deterrence, not focusing only on the defenders but seeing also variations in the challengers[14].

- Strategies depend on others’ strategies.

Interactions occur between strategies, when actors react to others and anticipate their presumed actions. This is where most of the examples of strategic surprises in international politics can be found. For instance, when a state believes that obstacles for an action are so high for an enemy, he does not prepare (or stops) to counter him. This prompts the enemy to put a lot of effort in overcoming such obstacles. On the other hand, a threat can be minimized because actors are prepared to meet it., and try to overcome it, sometimes successfully. Judgments about what strategies the others will adopt are central in decision-making, and here the significance of leaders and internal decisions comes out.

Both success and failure are determined interactively. This is why many intelligence failures are mutual, affecting both who takes the initiative and who is taken by surprise. U.S. did not expect that Japan would have attacked Pearl Harbor as they knew they would have countered strongly such an attack. But since Japan (and others) were more inaccurate in their perceptions of the world, American predictions were also inaccurate by consequence.[15]

Both success and failure are determined interactively. This is why many intelligence failures are mutual, affecting both who takes the initiative and who is taken by surprise. U.S. did not expect that Japan would have attacked Pearl Harbor as they knew they would have countered strongly such an attack. But since Japan (and others) were more inaccurate in their perceptions of the world, American predictions were also inaccurate by consequence.[15]

Interactions of strategies explain why something that should harm the actor, in fact benefits it. States may waste resources (by showing off unnecessary arms) to demonstrate they are rich enough to be careless about that. Such behavior weakens actors on their own level, but it produces success on the systemic level.[16]

- Behavior changes the environment.

In complex systems, co-evolution and co-adaptation occur. Actors changes the international system while adapting to it, and this becomes more hospitable to some of them and less to others. As already seen, this challenges the clear identification of causes, as changes can be caused by both actors and environment. Consequently, international system never settles down to a fixed state, as evolving dynamics prompt continuous transformations into it. New environment will not allow past elements to continue to live in it, and then actors themselves change, setting off a circle of effects. In political world’s disputes, policies and actions reshape landscapes and affect actors within the environment. As protests rise, new directions are instilled in politics and public response may differ from what protesters intended; nevertheless, they did change political environment.[17]

On the other hand, preferences, interests and capabilities of actors are changed by interactions they have with one another and with the system itself. Thus, environment influences actors’ behavior too. Arms races are a clear example of how an environmental situation of conflict and tension drives agents to increase their military capabilities, as they perceive a systemic constraint to do so without the choice of defection.

This stance takes into account the role of institutions and other international regimes in shaping actors’ interests and actions. States are situated in a certain history and have certain relations with these institutions, and they are inevitably affected by them, in bigger or smaller way depending on their position and interests.

Furthermore, interactions where actors change the environment help explaining various failures of deterrence. For instance, if Pakistan increases its nuclear capabilities, likelihood of Indian attacks should decrease, from the actor’s perspective. However, this decision would prompt India to preempt any Pakistan attack and to feel more accepted by world community as it would attack a nuclear power[18]. Moreover, deterrence moves can change opponents’ behavior and make deterrence more difficult to implement later on.

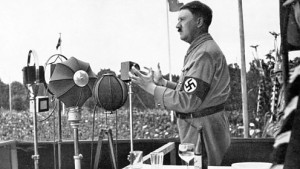

Leaders usually fail to consider this transformative power of their actions. “History is about changes produced by previous actions”[19], that shape the course of events throughout its own development. Statesmen believe to produce certain outcomes with their behavior, assuming all the other things being equal; yet they fail in their predictions as their behavior undermines and changes other things (i.e. environment). Hitler believed his enemies were “little worms”, but since Munich conference his own behavior made them changing preferences and decisions. Thus, Hitler failed to anticipate systemic consequences of his decisions[20]. Failure to appreciate the fact that actors’ behavior affects environment (which in turn affects actors) can occur among observers as well, driving them to underestimate the importance of actors’ influence. Systemic constraints are strong (e.g. conflict spirals) but they may have been created by previous actors’ behavior, who may have been unconscious of the later consequences of their decisions (and here the theme of unintended consequences becomes central again).

Leaders usually fail to consider this transformative power of their actions. “History is about changes produced by previous actions”[19], that shape the course of events throughout its own development. Statesmen believe to produce certain outcomes with their behavior, assuming all the other things being equal; yet they fail in their predictions as their behavior undermines and changes other things (i.e. environment). Hitler believed his enemies were “little worms”, but since Munich conference his own behavior made them changing preferences and decisions. Thus, Hitler failed to anticipate systemic consequences of his decisions[20]. Failure to appreciate the fact that actors’ behavior affects environment (which in turn affects actors) can occur among observers as well, driving them to underestimate the importance of actors’ influence. Systemic constraints are strong (e.g. conflict spirals) but they may have been created by previous actors’ behavior, who may have been unconscious of the later consequences of their decisions (and here the theme of unintended consequences becomes central again).

Actors’ actions interact to constitute the environment and change it, while actors are in turn changed by the alterations of the environment. This strengthens the interactionist perspective adopted: actions do not have merely one single and direct course of consequences, and all the actors and the system at play are involved in the formation of outcomes at any level (from the lowest to the systemic one). Individuals are constrained and formed by the system, and the system is affected by individuals’ choices as well.

Taking these three kind of interactions as the unit of analysis for IR clarifies the limits of approaches that consider states driven by external forces and ignore states’ capacity to affect external world. What follows is that circular effects can easily occur in international life (as actors respond to new environments they help to create). Security dilemma (increasing own security to decrease others’ security)[21] is a clear example of such a dynamic: states don’t trust each other and they seek to protect themselves against menaces. Such decisions may then create all new ranges of perils. Their fear of eventual attacks instills policies that prompts others to become real enemies, creating new (real) issues.

It would be a mistake to limit the analysis to just one isolated side of the interaction, either the state or the system or the individuals within a group. The whole range of interactions must be take into account[22]: interactions among states, states and non-state actors, groups and their internal elements, groups and system and so on. This breaks down the old mainstream division between domestic and international context, both meaningful for a sensible analysis. Moreover, this considers various concepts, previously seen as contrasting, such as power and preferences, security and cooperation. All these ideas play now a role in shaping actors’ behaviors and they can all affect the system and the states’ constraints, depending on the context and the specific situation in which they are historically collocated. Interests’ formation may vary a lot, and none processes should be excluded a priori in this theoretical perspective.

Such comprehensive approach to the problem of unit of analysis seems to counter other theories that explain partial sector of IR. They usually argue that regardless their partiality, they seek to explain “the important things” of international life[23]. However, as seen through concepts of ‘butterfly effects’ and the importance of interactions among all elements and system, there are no things such as “the important things” in international life. What is important may never be known until it shows all its effects, who may be delayed, indirect and unexpected, and even lot bigger than they should have been. The role of small right-wing protests cannot exclude for international outcomes, as they may shape public opinions in so many different ways giving unexpected outcomes, that they should be responsibly taken into consideration while observing international reality.

[1] See D. J. Singer, “The level-of-analysis problem in international relations”, World Politics, 1961, 14:1, pp. 77-92.

[2] Ibidem.

[3] See M. Doyle, “Liberalism and World Politics”, American Political Science Review, 1986, 80:4, pp. 1151-1169.

[4] See R. Jackson and G. Sørensen, Introduction to International Relations. Theories and approaches (5th ed.), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013, pp. 241-245.

[5] See K. N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics, Waveland Press Inc, Long Grove, 1979.

[6] See E. Diodato, (ed.), Relazioni Internazionali. Dalle tradizioni alle sfide, Carocci editore, Roma, 2003, pp. 150-189.

[7] See R. O. Keohane, “Neoliberal Institutionalism: A Perspective on World Politics”, in Keohane R.O., (ed.), International Institutions and State Power: Essays in International Relations Theory, Westview Press, Boulder, 1989, pp. 1-20.

[8] See R. L. Jepperson, A. Wendt, and P. J. Katzenstein, “Norms, Identity and Culture in National Security”, in Katzenstein P.J., (ed.), The Culture of National Security. Norms and Identity in World Politics, Columbia University Press, New York, 1996, pp. 33-75.

[9] See J. Milliken, “The Study of Discourse in International Relations: A Critique of Research and Methods”, European Journal of International Relations, 1999, 5:2, pp. 225-254.

[10] In the next section the differences of systems’ conceptions will be analyzed, and it will be shown that such poststructuralist critique cannot work against a complexity approach.

[11] R. Jervis, System Effects. Complexity in Political and Social Life, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 199., p. 35.

[12] Ibi, p. 40.

[13] Ibi, p. 43.

[14] Ibi, p. 42.

[15] Ibi, p. 45. Not all American analysts were so inaccurate, but these are the actual results anyway.

[16] Ibi, p. 48.

[17] Ibi, p. 50.

[18] Ibi, p. 54.

[19] Ibi, p. 55.

[20] Ibidem. This is strongly coherent with the presented Jervis’ account and reconstruction of events.

[21] See J. H. Herz, “Idealist internationalism and the security dilemma”, World Politics, 1950, 2:2, pp. 157-180.

[22] N. E. Harrison, “Complexity is more than Systems Theory”, cit., p. 37.

[23] J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, W.W. Norton and Company, New York, 2001.

Be First to Comment