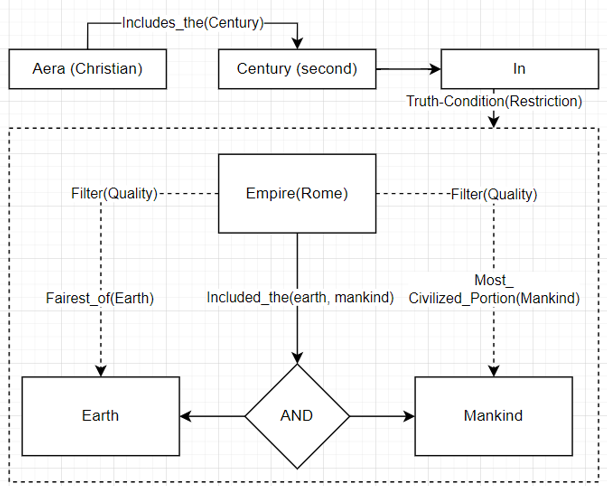

How does language connect to the world? A simple, ancient question that should hunt every serious scholar in any field. For example, what do we mean when we say, ‘The army fought bravely against Nazi Germany’ or ‘All crows are black’? How can we connect an ‘army’ to ‘braveness’ and its ‘fighting’ ‘against Nazi Germany’? What do we actually mean by ‘all crows’? No matter how one wants to tackle the problem, this is quite an astonishing open-ended hurdle that every new generation of thinkers must recalibrate or reframe.[1]

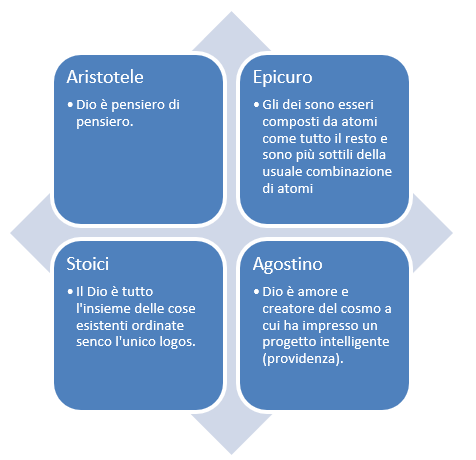

Plato started the quest because of his idealist conceptualization of knowledge, which was understood only as perfect in terms of access to the ideas which, in turn, must refer to the world somehow. However, how to connect his ideas to a specific ‘table’ is not an easy endeavor and Aristotle tried to reverse the process: we describe ‘tables’ given the knowledge we get from every specific table. But then, how can we have a general notion of tables? From where this ‘generality’ comes from and how can it be justified? Ultimately, these answers can be partially given reformulating the problem in terms of meaning. The meaning of the sentence ‘the table is black’ depends on the meanings of its constituent components. What does meaning mean? We need to clarify what the meanings of words (in theory, all of them, including prepositions, indexicals, and prepositions).

Interestingly, so-called idealist philosophers such as Renè Descartes and Baruch Spinoza reinterpreted the idealist vision in subjective terms. Plato assumed that ideas are external non-causal entities existing outside the phenomenon and the mind. They stay there eternally unmoving mysteriously able to give us a real glimpse of a stable world. Firstly, Descartes reinterpreted this concept within the subject itself: ideas are stable construction of the cognitive subject whose access is granted by direct introspection whose strength is supplemented by reason. However, the grasp of concepts can be independent from reason, which has the primary goal to make arguments based on those ideas and concepts. Of course, Descartes had the same problem Plato had; that is, how to connect ideas to the world. In his case, he had to make a brilliant and convoluted argument based on the alignment between ideas and the world granted by God and by the general architecture of cognition.[2] Spinoza, partially endorsing and criticizing Descartes, extended those lines of arguments: not only ideas can be explicitly grasped directly through a special direct introspection (intuition) but reason is the sole means to grant justification in elaborating new ideas.[3]