How does language connect to the world? A simple, ancient question that should hunt every serious scholar in any field. For example, what do we mean when we say, ‘The army fought bravely against Nazi Germany’ or ‘All crows are black’? How can we connect an ‘army’ to ‘braveness’ and its ‘fighting’ ‘against Nazi Germany’? What do we actually mean by ‘all crows’? No matter how one wants to tackle the problem, this is quite an astonishing open-ended hurdle that every new generation of thinkers must recalibrate or reframe.[1]

Plato started the quest because of his idealist conceptualization of knowledge, which was understood only as perfect in terms of access to the ideas which, in turn, must refer to the world somehow. However, how to connect his ideas to a specific ‘table’ is not an easy endeavor and Aristotle tried to reverse the process: we describe ‘tables’ given the knowledge we get from every specific table. But then, how can we have a general notion of tables? From where this ‘generality’ comes from and how can it be justified? Ultimately, these answers can be partially given reformulating the problem in terms of meaning. The meaning of the sentence ‘the table is black’ depends on the meanings of its constituent components. What does meaning mean? We need to clarify what the meanings of words (in theory, all of them, including prepositions, indexicals, and prepositions).

Interestingly, so-called idealist philosophers such as Renè Descartes and Baruch Spinoza reinterpreted the idealist vision in subjective terms. Plato assumed that ideas are external non-causal entities existing outside the phenomenon and the mind. They stay there eternally unmoving mysteriously able to give us a real glimpse of a stable world. Firstly, Descartes reinterpreted this concept within the subject itself: ideas are stable construction of the cognitive subject whose access is granted by direct introspection whose strength is supplemented by reason. However, the grasp of concepts can be independent from reason, which has the primary goal to make arguments based on those ideas and concepts. Of course, Descartes had the same problem Plato had; that is, how to connect ideas to the world. In his case, he had to make a brilliant and convoluted argument based on the alignment between ideas and the world granted by God and by the general architecture of cognition.[2] Spinoza, partially endorsing and criticizing Descartes, extended those lines of arguments: not only ideas can be explicitly grasped directly through a special direct introspection (intuition) but reason is the sole means to grant justification in elaborating new ideas.[3]

In modern times, classic empiricists tried to reduce these problems to the aggregation of sense data. For example, David Hume tried to reduce everything to single sense data points assuming existing in our minds and being able to point to objects existing somewhere else.[4] More recently, Rudolf Carnap and Willard V.O. Quine tried to go in the same direction.[5] However, Hume had troubles in explaining how our language works as it seems quite hard to understand how sense data are stably related to words and, through them, to the world.

More importantly, his problem is specifically how to understand the unity of such wildly diverse data points. He tried to explain ideas in terms of aggregation and pattern of similarity, but ultimately this is a circular argument. From where does this ‘unity’ come from? Why do we stably understand the sentence ‘all crows are black’ without even having seen ‘all’ crows? Indeed, even without knowing what a crow is, there is clearly a sense in which we can understand the sentence nonetheless, as Gottlob Frege pointed out in his philosophy of language.[6] Quine partially solved this issue through his clever conceptualization of language: it is language that is bringing order and unity to partially anarchic sense data stimuli. However, when it comes to general vision and understanding, it seems to me that Quine primarily refurbished the original Humean vision of meaning through very intelligent philosophical specifications. However, he still seems to downplay the problem of unity and epistemological centrality of the subject proper operations on the stimuli.

This was not a problem for Immanuel Kant’s metaphysical-epistemological standing. He had a clear reply on the fact that order is brough by multiple convoluted operations of the cognitive subject, starting from the senses and ending to the intellectual operations whose results can be used and extended by reason.[7] However, he did not fully appreciate how language plays a clear role in this picture and how memory is required for all of them. Quine is right in pointing to language as a key component of our general capacity to describe the world and, without it, it would be unthinkable for us to conceive the world as we do. Indeed, it was Alan Turing who realized that, essentially, a thinking machine is more a gigantic memory than a computational powerhouse as the computation requires memory in the first place. His very notion of computability through Turing Machines should prove this point even further as the computation itself at best is equally important to the length of the symbols that can be manipulated and stored or deleted. As Turing pointed out, machine thinking is all about memory and all the history of Artificial Intelligence seems to confirm it,[8] beyond the fact that Kurt Godel seemed to have proved that computation plus memory is never going to be enough to replicate all mathematics (and etc.).[9]

All in all, this is not intended to be an exhaustive essay but a firm starting point for later refinements and, in this regard, this discussion is just to point out from where some of the following concepts and ideas come from. In general, my understanding is grounded by Kant’s theory of cognition and Spinoza’s metaphysics, but specific ideas and objections were paramount, for example the developments of formal logic and set theory, Wittgenstein’s vision of language as part of life, and Quine notion of meaning. To contemporary purists, this seems to be a pastiche of wildly different traditions and debates. I disagree so far as my purpose here is to give what I think makes sense for my own sake and purposes and not to engage in some minor development of already sufficiently esoteric philosophy. Whoever wants more of that can directly go to different places. In this regard, this analysis intends to show how memory plays a major role in defining meanings and how this relates to other fundamental semantical problems.

Meanings and Memory – What We Mean with Words?

Natural language is a ‘library’ of different ‘books’ unified by the generality of its expressivity.[10] Here with ‘library’ I mean specifically a subsection of the whole where further specifications are given for the use of words or the interpretation of how to use them. An encyclopedia composed by all vocabularies of different jargons for different scientific or unscientific disciplines is what natural language does with its specific jargon and idiolects. Indeed, its outstanding power relies on its simplicity and elegant capacity to reinterpret the same words differently depending on the specifications of a given context. A context can be understood as the specific relations between a given cognitive subject S and the external conditions of the world C such as for each C there is a set of semantic rules R to be used for formulating appropriate statements in C. However, natural language without meaning is empty and, indeed, unthinkable.

Especially at general level, every single word can be interpreted in multiple ways both depending on its meaning and on how it was actually stated (what Frege identified as beyond both sense and meaning). But even limiting ourselves to names and predicates, they mean different things in different contexts. For example, ‘memory’ can mean something we remember, the function of a given area of the brain and a game. There is nothing wrong with this. Indeed, this is the only way to avoid the endless multiplication of words to a point where our human capacity to record information would be easily exhausted. Instead, the mind solved the problem through a combination of specific rules of interpretation over single words in specified contexts. Clearly, these rules must be known but one rule can be endlessly reused. The founders of formal logics thought this was a serious flaw in natural language, as effectively it can lead to problems. This could be true, but how can we state those problems without natural language itself?

Elsewhere I already defended the idea that the underneath operations behind natural language are set theoretical and logical in nature. That is; to make sense of sentences and to understand them in Wittgensteinian fashion (we understand a sentence if we understand its truth-condition), we need to assume quite a lot of set theoretical and logical work of natural language. In this place, I will focus, instead, on what I think meanings must be, restricting my attention to names and predicates, although prepositions, articles and adverbs can be better appreciated looking at what they do in set theoretical and logical terms.[11]

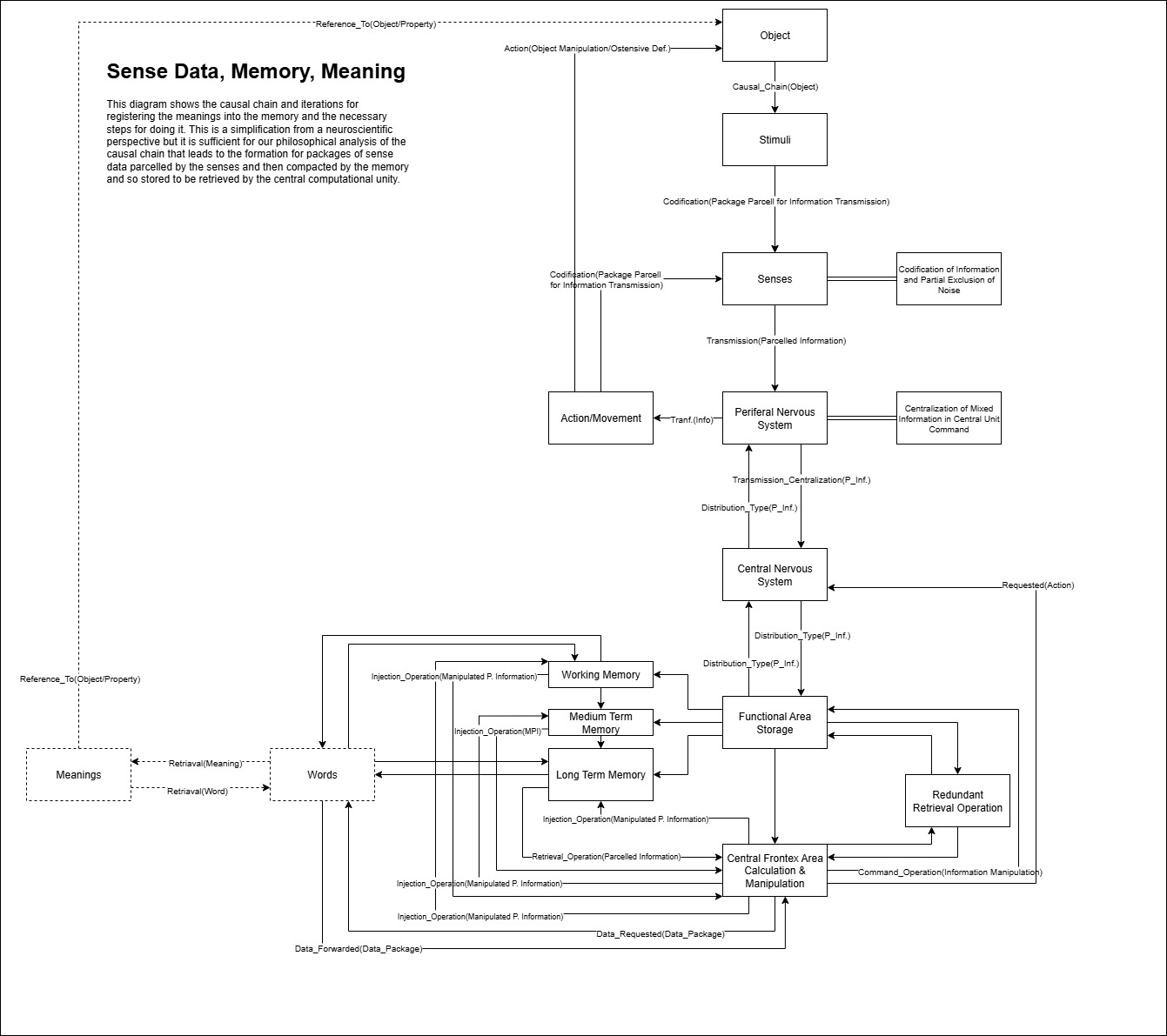

The association of a given word to its meaning must be a very complicated operation for the mind, here intended as the computational capacity of the brain.[12] If we stick with our Kantian model of the cognitive subject, at least partially compatible with Quine’s description of stimuli exposure, the senses play major role in encoding and sifting the data collected even before they are passed to the upper structures of the brain. The data are parceled and codified in a way that the mind can operate.[13] We know that this basic cleaning of the stimuli must happened by empirical experiment, but we can deduce it by the simple fact that any electric signal must acquire a form such as it is readable by the mind.[14] The sense data so encoded must be sifted somehow as many parallel stimuli are competing for the mind’s access.[15] Then, specific areas of the brain aggregate and sort the information so encoded and they send it to the memory type (short or long term) depending on how the information was recorded depending on the information forwarded (e.g. procedural, semantic, visual etc.).[16] Importantly, the sense data are encoded as packages of electric stimuli that must be assumed as discrete as, after all, it is the nature of electricity to be composed of discrete particles and sets of neurons store the information in discrete ways. The sense of continuity must be produced by the speed and continuity of the stimuli in combination with the continuity of the mind’s operations.[17] Although this is a very short and logical reconstruction of a far more complicated process, it already shows multiple critical aspects of how we could form the meanings of words.[18]

Any given word w must have a meaning m associated to it to make sense and to be used appropriately in each sentence p. Both w and m must be stored somewhere in the long-term memory M. However, w and m are distinct, by definition. The meaning of the word ‘dog’ is not a dog: the meaning of ‘dog’ is all we know and assume about a given animal at a given time.[19] Moreover, w is composed of a sound and by a series of discrete components (letters). Instead, the meaning m of w has nothing to do with the sound or letters, as it is related to the sense data stored somewhere in the memory and then associated to w, as predicated by Quine.

Every meaning must start somewhere and, necessarily, it is about a given set of sense data P(d1…dn) that are aggregated into a unity by the mind and progressively associated to a given word w, as suggested by Quine.[20] However, the package of sense data P(d1…dn) must be assumed open-endedly solidified into a unity that comes back every time the word w is evocated. Let’s assume this is not the case; then w would evocate any given package of information Pn(d) or nothing. Either case, w would fail to be appropriately used in any given sentence and context. Therefore, w must elicit a very specific package of sense data whose extension is defined by P(d1…dn). Notably, P(d1…dn) is composed by any sense data type and the only explicit requirement is that this package is appropriately stored by the memory and retrieved when w is elicited such that there must be stable causal relation CR that connects w to m:

∀(w)∃(m)CR(w,m) = True

This brings us to a series of fundamental considerations.

Firstly, if m is somewhat defined by M(P(d1…dn)) = True,[21] that is, the memory M stably store and retrieve P(d1…dn) when w is elicited, considering that the nature of d1…dn entirely depends on what the sense recorded, then, there is no specific limit to the complexity and dimension of m because there is no restriction over the type of sense data that can be part of P and then associated to w. This should make quite a lot of sense. Notably, as we will clarify below, w is literally the linchpin between other operations of the mind and m. Importantly, the role that the word w is playing is to contribute to the unity of what we capture in the senses, and we solidify as m. The richness of the meanings of words entirely depends on the sense data unified, classified and associated to w. This means, of course, that any meaning m1 of any word w1 will likely overlap other meanings of other words w2 whose meaning m2 is at least partially including part of P(d1…dn). In other words, if the meaning m1 of w1 is P1(d1…dn) and if the meaning m2 of w2 is P2(d1…dn), if they are overlapping, then P1(d1…dn) ∩ P2(d1…dn) ≠ Ø. This brings us to conclude that: (a) a given cognitive subject S store in their memory M a total of meanings m1…mn such that m1…m2 constitute a partially overlapping constellation of sets of shared sense data whose shape must resemble a multidimensional 3D jigsaw puzzle; (b) the specific linguistic capacity of the subject is directly in function of their capacity to recall meanings through words and vice versa.

Another fundamental aspect of this theory of meaning is that given a meaning m of w defined by the encoded data P(d1…dn) is open-ended in what constitute P(d1…dn). Namely, the data encoded P(d1…dn) can be of different types and include sense data in raw form but also semantic packages. For example, any single meaning we have almost invariably includes semantic information stored as such. As different types of data packages are stored differently, as ultimately any given piece of memory is distributed across the brain, meanings are by definition wildly different aggregators of different types of packages. This is partially explained by and reinforces the principles we already outlined: a given meaning m works as a tiny model of an entire piece of reality whose storing is distributed and overlapping with other meanings. Again, Quine is right in thinking of networks of beliefs as meanings overall and redundantly reinforce one another. Of course, this could lead to error and glitches, such as Vesperus and Phosphorus, the two words whose meaning is the same star. However, the problem of analysis is easy to solve within this framework: astronomical discovery should lead to the identification of a common meaning between two different words and nothing more.

Focusing our attention on what just proposed, let’s consider the meaning of the word ‘dog’. This word must elicit some semantic memory as, by definition, we are eliciting the sense data clustered through it. This means that there will be multiple sentences in which we know if ‘dog’ is properly or unproperly used from a merely syntactical perspective. Then, we will have a series of propositions about ‘dog’, which will have them as an object or subject of the propositions. However, to let the mind run the set theoretical and formal logic operations that allow us to formulate those sentences in our mind, we need to assume that other meanings are known, so eliciting other memories. That is; the proper use of the word ‘dog’ implies an open-ended list of other semantic items also acquired. However, we are able to sift appropriate use of the word depending on the sense data associated to ‘dog’. For example, we can elicit the memory of the sound that that animal does. Interestingly, however, when we formulate a general statement such as ‘all dogs bark’ what we are really doing is making a leap from what we know about specific dogs to the whole set of dogs without committing to it.[22] What we are really expressing is something closer to: ‘for all we know about what we mean with ‘dog’, all the items of the set of dogs have the capacity to bark as a property’. However, when we elicited the ‘barking’ we likely elicited a specific sound and, likely, a specific visual representation of a dog we have known or seen. Therefore, the meaning of ‘dog’ is this complex system of information clustered around one specific word. Thinking that we can disentangle a ‘pure’ notion of ‘dog’ from these different types of memories is simply unthinkable and illogical.

Hence, generalizing from the previous point, any meaning m is the set of all the different types of sense data packaged and associated to the word meant such that

m = (semantic data, visual data… any data type) ∈ P(d1…dn)

This seems to suggest that m can be more or less expanded depending on the dimension and sheer quantity of the data stored. This explains why an expert means much more with the same words that a layman: a veterinarian uses the word ‘dog’ with more meaning than an average person. Moreover, we are indeed talking about data here because, according to the conventional definition of information, at least data plus meaning is information.[23] In this sense, according to our theory, data plus unified memory is meaning, and information is an appropriate combination of meanings (e.g. a well formulated sentence) which are structured, unified and stored sense data.[24]

Immediate Consequences of the Theory of Meaning

A fundamental consequence of understanding meanings in this way is that meanings are parceled in such a way that they can be and are altered through time. Indeed, a given m defined by M(P(d1…dn)) depends on what the memory can store and retrieve when w is actually directly or indirectly elicited, where ‘indirectly’ here can be because of a close word w2 was elicited and whose meaning overlaps with w. Moreover, the construction of m is completely causally closed as every step of the process is, indeed, completely exhausted by the interaction between the subject’s mind operations, memory and the sense data coming up. This means that any given w is defined by their m at any given time t, where they can be slightly differently defined at any given successive time depending on what stored and retrieved by the memory. In this regard, both Kant and Quine were right in their conceptualization of meaning as unity (Kant) of sense data stimuli (Kant and Quine) stored in the memory for mind’s operations. However, it should be now clearer how both missed the absolutely essential role of memory in meaning creation and unity through time.[25] Memory is not the exclusive source, but it is the means of meanings.[26]

Let’s pay attention to the active role that all the neurological system is playing when establishing a new meaning or changing an already existing one. As we have already seen, the first step of the process is done by the peripheral neurological system in parceling and sifting the sense data. Then, the package of sense data is codified in a way that is tractable by the specific type of memory involved in the storing process. This is not an innocent component of how meanings are established as there is a clear selection and integration process in two different ways: there is an expansion of the m, if already existing (additive operation); or there is a subtraction of portions of m which turned out to be incorrect or contradictory or they simply get subtracted by misuse. Either way, the updated version m at t2 must require a consistency and compacting operation as otherwise there would be glitches in retrieving m and it must run through an iterative process. That is,

m = P1(d1…dn) – P2(d1…dn)

P1(d1…dn) at t1

P2(d1…dn) at t2

—

P1(d1…dn)∩P2(d1…dn) ≠ Ø [N][27]

This means that memory types are playing an active role in determining how m will ultimately be stored in parallel depending on how many different data types are involved in the process. Without the active operation of the memory, our meanings would look significantly different, which brings immediately to ask an important question.

How such a wildly diverse series memories for each meaning notwithstanding yield a sense of general unity in our vision of the world.[28] Differently from Hume or George Berkeley, for example, we have an easy answer: unity is brought by language and words which elicit that aggregate of sense data through semantic operations plus the continuity of the mind’s operations across both sense stimuli, manipulation and memorization. Exactly as Quine was arguing, this is what language brings to the table as it is, indeed, more stable than the meaning beneath it. This works exactly because the any word w is mechanically and causally linked to its package of sense data P(d1…dn), that is, their meaning such that the meaning of a word is the function of retrieval of all or part of the sense data stored as part of it. Once again, we can admire the elegance of the mind in construing this structure where there is request for explicit awareness of all the sense data associated with a given word but it is elicited only when requested for linguistic or visual or any other operation and it is silent otherwise. This also explains why language renders ideas one by one, but we have a clear perception of a much wider and parallel awareness of what is actually entailed. When we say ‘my neighbor’s dog is barking’ we mean much more than what stated.

Once a meaning m of w is solidified and stored into memory, then the intellect can start to make its operations. This should be now clearer on why there is a substantial agreement over the fact that cognitive subjects bring unity into the sparse sense data. They do it in different ways; firstly, through words and through aggregations of their meanings. And given the fact that meanings essentially are unconceivable in isolation, this creates a sense of unity within the subjective cognitive space: all the intellectual operations are indeed slicing specific meanings, clarifying portions of them or deleting mistakes, very similarly to what Kant’s intellectual categories do as part of their operations in combination with the actions of reason. The sifting operation is more appropriately what reason does when scrutinize their memory through semantic or visual analysis. In this regard, any word w2 whose meaning m2 expresses a subsection of another meaning m1 of w1 is immediately available to the mind in sentences where w1 are properly used and it would see it as a natural connection through the meaning of it. For example, if w2 is ‘tail’ and w1 is ‘dog’, the mind will clearly see that m1 ∩ m2 ≠ Ø. Interestingly, depending on how well a given subject knows about tails and other meanings associate to other words related to animals, that is, how extended P2(d1…dn) is, they could draw the inference that m1 → m2 but not m2 → m1 only assuming that P2(d1…dn) is extended enough to show that ‘tail’ is a portion of other animals as well. This should clearly show, once again, how the meanings of the words are related and intersect and how they are directly linked with the sheer amount of we have about portions of the world.

The last problem that should be addressed is how words connect to the world according to this theory. The answer should be simple. They are causally directly related to portions of the world that are unified by the subject into specific meanings to be reused across time and named through language. In this sense, we can link this idea to Alvin Goldman causal theory of knowing (as a model), Jerry Fodor’s theory of mind and, more importantly, Baruch Spinoza’s causal theory.[29] That is, a given object o causes the meaning m through P2(d1…dn), such that

∀(m)∃(o)C(o,m) = True IFF m would exist without o and it exists with o [N][30]

However, there must be another causal chain that links m to its correspondent word w such that

∀(m)∃(o)∃(w)C2(C1(o,m), w) and w ∈ M [N][31]

It is quite obvious that every meaning acquisition starts with sense data unless the meaning of a word is naming a subsection of an already established meaning (such as ‘tail’ once ‘dog’ is acquired etc.) or some further analytical operation is done by the mind (e.g. creating a connection between the word ‘dog’ and ‘barking’).

Thus, the words connect to the world because the subject S can point back to the world. It is S’s operations and actions that can link back a word to the original object through its meaning. They are literally proceeding backwardly from the word to the meaning back to the world. The question can be answered only in this order, although proper purposeful action does not require this chain as it does not require semantic elaboration or its awareness:

∀(m)∃(w)∃(o)C2(C1(w,m), o) [N][32]

Ultimately, thanks to the mind operations and stability of memory’s sense data packages, a given subject is able to translate into action what they think or to indicate what is the meaning of a given word pointing to a given object or property. It is the subject that brings unity and stability to the wilderness of sense data and it is also the subject that connect words to the world through actions or through associations between meanings and objects or properties and, ultimately, everything just described has a direct causal relationship such that we can logically reconstruct that nothing is created, everything transforms but nothing is destroyed.

References and Meanings

In this theory, there is a neat distinction between references and meanings. Meanings are intended as models of reality stored into the subject’s memory and labelled through a word or a series of words. In this sense, the mind accesses the meanings through the memory and when it calls them, it can contemplate it as present and it can operate actions on them. However, these actions cannot be operated when considering the objects to which the meanings refer to. Hence, words refers to objects through their meanings and the references of words are the objects or properties to which words point to.

The paradox of the analysis is solved as two words can have the same reference and different meanings depending on how a given subject construed them.[33] Without knowing that Vesperus and Phosphorus are the same star, it is possible for a subject to construe two different meanings for them. This is not only possible but unavoidable, and the solution can come only through scientific scrutiny, which changes the meanings of the two words discovering that they both refer to the same celestial body. Interestingly, though the reference of two words can be the same, they can still have two different meanings. For example, let’s assume that a subject attaches a given emotion e to Vesperus but not Phosphorus. Even when they realize that they are indeed the same star, the meanings are not immediately updated and only under the assumption that the subject can unify them then there is a unity of meanings as of reference. But here we are entering the realm of cognitive psychology and not of philosophy. Philosophically, it is sufficient to say that it makes sense falling under the analysis paradox as our cognitive capacity can create mistakes and glitches in our network of meanings and words exactly because we need appropriate sense data to change them. Considering the limitations and imperfections of our alignment with the world, we cannot ask for more and, at the same time, we should be impressed by our capacity to mirror so often what is indeed the case in the world.[34]

Causal Closure, Extensionality and Making Sense of Language as a Means of Meaningful Communication in the Appropriate Context

This theory should show how meanings are causally determined by external objects whose reconstruction in the mind is fixed through words and memory. All the single operations of the mind and body are of causal nature, and the meanings are directly tied to the world. Hence, the words are the instrument for describing the world as it is or imagining different words. This is indeed possible exactly because there is no direct commitment for the mind to always use the words as ways to access models of the world through their meanings. We could simply run thought experiments or any similar intellectual operation without any need to connect the words to the world. At the same time, it remains critical the capacity of the mind to go back to the world and certify what is the state of affairs and what is not. The mind and the world are tied together by the principle of causal closure.[35]

In this way we can solve the difference between intensionality and extensionality. The extensionality of a given meaning is simply the extension of its sense data package, where the intension is to all the mind is able to apply it. For example, the actual extension of the predicate ‘red’ includes all the items stored in the memory as ‘red’ and as all the objects in the visual field that are identified as such. However, the mind is clearly able to apply the predicate to other objects that can be only part of their imagination, for example, an idealized cube. In other words, the subject is able to imagine alternative possible words in which the predicate is applied to different objects so extending the predicate not only to the actual but to the possible.[36]

It is possible to object this theory that is entirely subjective and all meanings are grounded on the idiosyncratic mind’s arbitrary to fix the sense data produced by the senses and then stored in unities by the memory. However, there is an elegant reply to this objection. There is no question that I learned the word ‘dog’ from different sense data than my mother: she learned the same word far before I was born. My meaning of the word and her meaning of the word can be different but they are united by the same word that encapsulates the same meaning induced by objects of the same class. Moreover, during my learning of the word ‘dog’ I received external instruction on how appropriate I was using that word through a system of trial and error, where the error was identified and somewhat discouraged through (tendentially mild) pain. Then, even with different sense data packages, we both use the same word for the same references. This all block is very similar to what Quine defended in Name and Object.[37] In this sense, a vocabulary is a system of definitions through which a given linguistic community fixes the rules for appropriate usage of words assuming that those definitions are translations over sense data packages that overall overlaps more than not most of the time.

Finally, we are able to understand each other more than not in ordinary circumstances. What this means is that we use the same words for subjective meanings whose reference is the same and we are applying similar rules of interpretation given the context of use. Given two subjects S1 and S2, for any given sentence uttered by S1, S2 retrieves the meanings of the words through their memory eliciting the interpretation of them through the rules of interpretations for the given context also through the memory and then producing a sentence or an action as a result. When S2 is not able to understand one word or a sentence then their mind elicits a reply requesting elucidation. A form of elucidation is through ostensive definition. The two subjects will be unable to communicate or because they are not sharing the same vocabulary or the meanings of the words are interpreted through different contextual rules or simply one of the two subjects did not learn specific contextual rules for interpreting S1 words. For example, S2 can be layman in a physics conference and they are not able to understand what ‘speed’ or ‘locality’ means in quantum mechanics as those words usually means something different.

How Idealist Understanding of the World are Conceivable and So Their Opposite

Idealist and realist are tied together by their language and by the fact that their minds work in a similar way. Where they diverge is in the actual generalization over the conception and source of the meanings. In this regard, what it is reasonable to believe is that they extremize two parallel tendencies. The idealists only assume that the meanings are sourced by the mind and projected to the world, as if the world has nothing to say about them and everything is found inside the mind. There is a sense in which this is true, if we consider that our meanings are models of reality whose existence is tied to the mind’s operations independently on how the external world is. It is also true that we did not learn the basic rules of the intellect and reason, as they are given to us by the mind’s machinery before any sense data was introduced to us by the senses, although this process starts very early on. In addition, philosophical speculation and fiction use words eliciting meanings independently from their immediate connection to the references. We do this all the time and we live as much in our minds as in connection with the world. However, it is absolutely mysterious how the world can be described as it is without assuming its independent existence and the sheer recognition that we know about the world through the world alone. Physics proved this feature beyond further question. Hence, what idealists assume is not unsound but unilateral. They capture something real, but they go beyond what we can say it happens.

Similarly on the other side, realists usually are too closely tied to the world and their causally determined meanings to accept that the mind plays the major role in the formation of meanings. But we have already seen that the mind and body combined contribute to shaping the meanings and memory plays a major role in creating the shape and contours of the sense data stored and associated to any given word. Hence, the predominance of the word and of causal relation determined by the objects in the first place seems to go too far in the other direction, as if subjects are just prone to passivity without active collaboration of multiple mind’s faculties which only make possible the existence of meanings.

In this line of thinking we can conclude that this is another form of the theory of eternal truth, as it commands that any theory has a core of truth that does not have to go beyond the threshold of what can be predicted, determining a unilateral and sterile vision of the world.[38] This theory outlines how words are tied to reality through the causal chain that produces the meanings, and, through them, we are able to think through words and actions.[39] As I always believed, any philosophical endeavor is both a conceptual and semantic operation and, as such, it must be translatable in action as, otherwise, philosophy is pointless.[40] In this sense, this theory tries to show how we are anchored to the world as much as we are not.

[1] In line with the theory of ethernal truth, see Pili, G., (2017), “La storia come libera creazione delle verità eterne”, Scuola Filosofica, available at: https://www.scuolafilosofica.com/5915/5915

[2] Descartes, R. (2016). Meditations on first philosophy. In Seven masterpieces of philosophy (pp. 63-108). Routledge; for a commentary, see Pili, G., (2011), “Renato Cartesio – Vita e le Meditazioni Metafisiche”, Scuola Filosofica, available at: https://www.scuolafilosofica.com/661/descartes and Pili, G., (2011), “Riflessioni di storia della filosofia: teoria della verità e dell’errore nelle Meditazioni Metafisiche”, Scuola Filosofica, available at: https://www.scuolafilosofica.com/684/riflessioni-di-storia-della-filosofia-teoria-della-verita-e-dell%E2%80%99errore-nelle-meditazioni-metafisiche

[3] This is more complicated than this but this is sufficient for our scope and purposes.

[4] Hume, D. (2000). A treatise of human nature. Oxford:Oxford University Press.

[5] Specifically in Carnap, R. (1998). Der logische aufbau der welt. And Quine, W. (1976). “Two dogmas of empiricism.” In Can Theories be Refuted? Essays on the Duhem-Quine Thesis (pp. 41-64). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, Quine, W. V. O. (1960). Word and Object, Cambridge: Massachusetts.

[6] Frege, G. (1948). “Sense and reference”. The philosophical review, 57(3), 209-230.

[7] See Pili, G., (2020), “Capire la “Critica della ragion pura” di Immanuel Kant”, Scuola Filosofica, available at: https://www.academia.edu/38740822/Capire_la_Critica_della_ragion_pura_di_Immanuel_Kant

[8] Although, funnily enough, it is clear that he was also simplifying significantly.

[9] Smullyan, R. M. (1992). Godel’s incompleteness theorems. Oxford University Press, Gödel K., (1951), “Alcuni teoremi basilari sui fondamenti della matematica e le loro

implicazioni filosofiche”, in Gödel K., (1995), Scritti scelti, Bollati Boringhieri, Milano. Pili, G., (2014), “Cosa ne pensava davvero Kurt Gödel?”, Scuola Filosofica.

[10] Pili, G., (2024), “Natural language and set theoretical and formal logic reductions”, Scuola Filosofica, available at: https://www.scuolafilosofica.com/12145/natural-language-and-set-theoretical-and-formal-logic-reductions

[11] Pili, G., (2024), “Natural language and set theoretical and formal logic reductions”, Scuola Filosofica, available at: https://www.scuolafilosofica.com/12145/natural-language-and-set-theoretical-and-formal-logic-reductions

[12] For a defense of a functional distinction between the two, see Pili, G., (2021), “The Principle of Transposition – The Untold Story about History”, Scuola Filosofica, available at: https://www.scuolafilosofica.com/11042/principle-of-transposition and Pili, G., (2025), “Levels of Human Action – Stages and Interplays of Human Reality”, Scuola Filosofica, available at: https://www.scuolafilosofica.com/12440/levels-of-human-action-stages-and-interplays-of-human-reality

[13] Vaidya CJ, Zhao M, Desmond JE, Gabrieli JD. Evidence for cortical encoding specificity in episodic memory: memory-induced re-activation of picture processing areas. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40(12):2136-43. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00053-2. PMID: 12208009.

[14] Connelly WM, Laing M, Errington AC, Crunelli V. The Thalamus as a Low Pass Filter: Filtering at the Cellular Level does Not Equate with Filtering at the Network Level. Front Neural Circuits. 2016 Jan 14;9:89. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2015.00089. PMID: 26834570; PMCID: PMC4712306.

[15] Ibid.

[16] There are somewhat different classifications of memories and a philosophical analysis would be useful to fully understand whether there are overlapping concepts or confusions, that all being said, see Psychology Today, “Types of Memory”, Psychology Today, available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/basics/memory/types-of-memory

[17] It is not as important establishing how concretely this is true and if electricity is a flux or a discrete subdivision of particles. The whole point is that the neurons are numbered and isolated and memories are based on them. It is clearly the continuous flux and speed of mind operations that create the sense of natural flow we constantly perceive.

[18] McKenzie S, Keene CS, Farovik A, Bladon J, Place R, Komorowski R, Eichenbaum H. Representation of memories in the cortical-hippocampal system: Results from the application of population similarity analyses. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2016 Oct;134 Pt A(Pt A):178-191. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2015.12.008. Epub 2015 Dec 31. PMID: 26748022; PMCID: PMC4930430.

[19] We will see why we are referring here to meanings in terms of time sensible entities.

[20] See, for example, the early chapters of Word and Object.

[21] That is, m ∈ M.

[22] We are not really committing to say that all dogs bark but only that it is a property of the set of dogs that to bark. But we wouldn’t change that statement even when considering that there are dogs that cannot bark for malfunction or illness etc..

[23] According to Luciano Floridi, information is meaningful truthful data, for a classic of his elaboration, see Floridi, L. (2005), “Is Semantic Information Meaningful Data?”. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 70: 351-370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1933-1592.2005.tb00531.x

[24] For a debate, see Sequoiah-Grayson, Sebastian and Luciano Floridi, “Semantic Conceptions of Information”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2022 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2022/entries/information-semantic/>.

[25] It is remarkable how memory played somewhat a minor role in both rationalist and empiricist thinkers across the ancient and modern age, Kant included.

[26] To be clear, Kant is able to consider many points we are making and his theory, on which this one is based in many ways, is able to accommodate, for example, the fact that we have a unity of perception through time as he does when he tackles the self-perception and the I think etc.. However, as Quine would have remarked, Kant’s conception does explain what is below language but not language itself. Quine, on another hand, does not consider sufficiently the problem of unity and how memory plays a key component into the process.

[27] What this all says is that a given meaning of a given word changes across time depending on the sense data that is actually stored in the memory.

[28] I called ‘vision of the word’ as the set of all the beliefs that a given subject S has at any given time. It is partitioned between factual beliefs, dispositional beliefs, normative beliefs and sentimental or spiritual beliefs. The analysis can be partially found in Pili, G., (2015), Filosofia pura della Guerra, Roma: Aracne, chap. 5 and in my unpublished Pili, G., (2012), ‘Theory of Society’, Unpublished.

[29] Goldman, A., “A causal theory of knowing.” The journal of Philosophy 64, no. 12 (1967): 357-372; Adams, Fred and Ken Aizawa, “Causal Theories of Mental Content”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2021/entries/content-causal/, Fodor, J., 1990a, A Theory of Content and Other Essays, Cambridge, MA: MIT/Bradford Press, and Spinoza, B. (2006). The essential Spinoza: Ethics and related writings. Hackett Publishing. For a reinterpretation of Spinoza’s metaphysics in Kantian terms, see Pili, G., (2016), “Libertà, volontà e legge morale: una posizione causale neo-kantiana della moralità”, Scuola Filosofica, available at: https://www.scuolafilosofica.com/5538/liberta-volonta-e-legge-morale-una-posizione-causale-neo-kantiana-della-moralita

[30] This says that for any meaning m there is at least an object o such that there is a causal connection between o and m. Instead, the truth-condition poses a counterfactual restriction and a sensibility condition such that the meaning wouldn’t exist otherwise.

[31] This says that a given word must be causally connected to its meaning which, in turn, is causally connected to an object. In practice, we know that multiple objects can be involved in the acquisition process of the meaning but this is beyond the point.

[32] This says that a given subject identifies o as the meaning of a given w through m through a causal chain that starts with w and ends with o. Notably, we can even require that there is an action over o (e.g. pointing out with a finger, moving the right object etc.). It is clearly unrequired so we don’t give another formula to describe this state of affairs.

[33] For an analysis of the paradox of analysis, see Nelson, M. (2008). Frege and the paradox of analysis. Philosophical Studies, 137(2), 159-181; Pili, G., (2010), “Il paradosso dell’analisi”, Scuola Filosofica, https://www.scuolafilosofica.com/525/paradosso-dellanalisi, Clark M., I paradossi dalla A alla Z, Raffaello Cortina, Milano, 2004.

[34] But I conclude that this idea is based on an ancient conception I developed in 2010 when I was trying to solve the paradox of analysis, when I argued that the problem raised not because of the references or Fregean senses and meanings, but because we process meanings differently even when they point to the same object. Then it was said less elegantly, but the idea is the same.

[35] For another application of the same principles, see Pili, G., (2025), “Levels of Human Action – Stages and Interplays of Human Reality”, Scuola Filosofica, available at: https://www.scuolafilosofica.com/12440/levels-of-human-action-stages-and-interplays-of-human-reality

[36] This is at least partially what Saul Kripke had in mind when he stated that, in his own accounts, possible words are a way to conceive reality, not an objective series of alternative universes. Kripke, S. A. (1980). Naming and necessity (Vol. 217). Oxford: Blackwell.

[37] Quine, W., (2013). Word and object. MIT University Press.

[38] Pili, G., (2017), “La storia come libera creazione delle verità eterne”, Scuola Filosofica, available at: https://www.scuolafilosofica.com/5915/5915, Pili, G., “Life as an Open-Ended act of Creation – Or Why Life is Unsolvable”, Scuola Filosofica, 2023, https://www.scuolafilosofica.com/11416/why-life-is-unsolvable

[39] This is in line with what many essays I publish or not.

[40] This was the same attitude of the greatest, classic philosophers and Immanuel Kant – of all! – reiterated this very point in his introduction to logic.

Be First to Comment